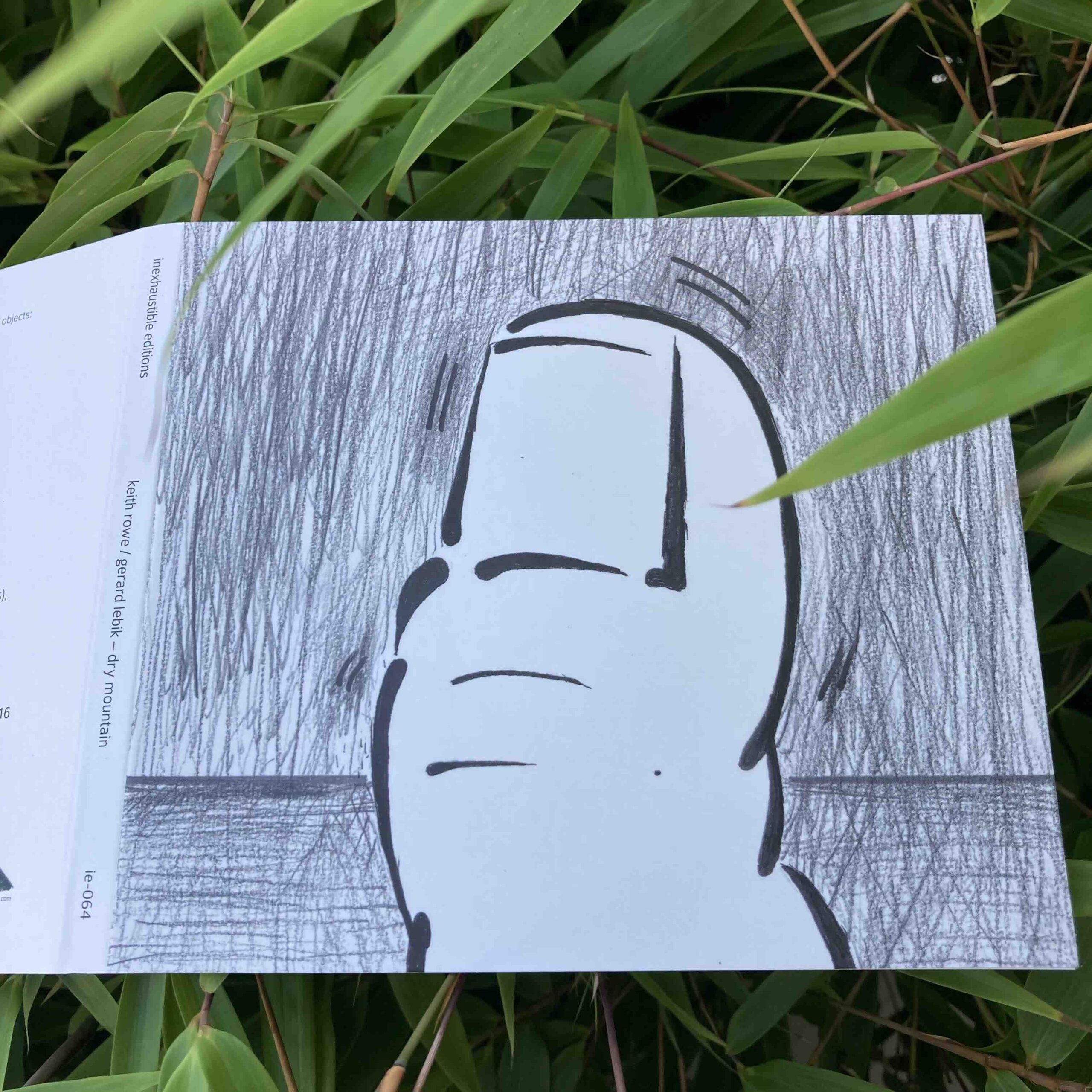

Keith Rowe / Gerard Lebik - Dry Mountain

Dry Mountain

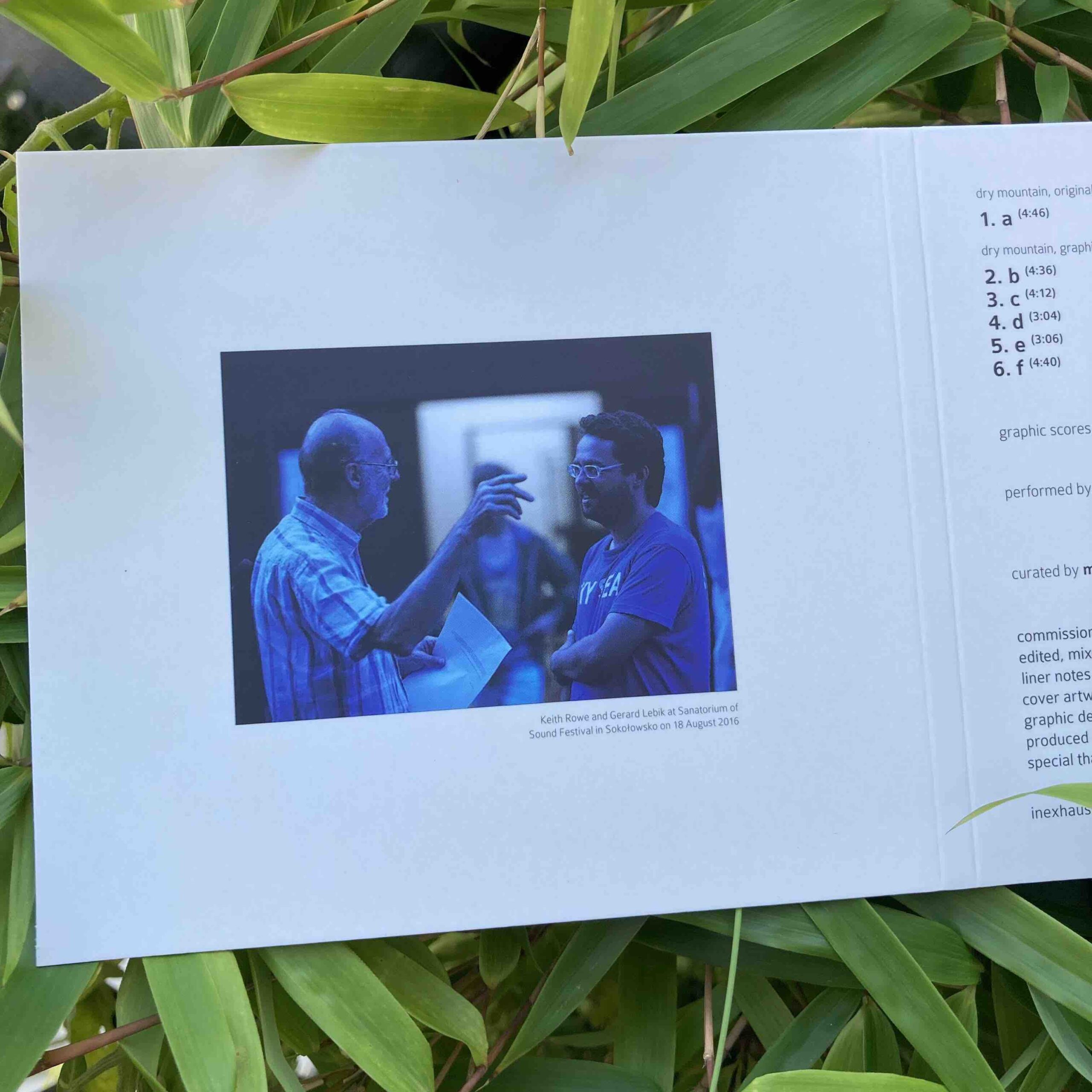

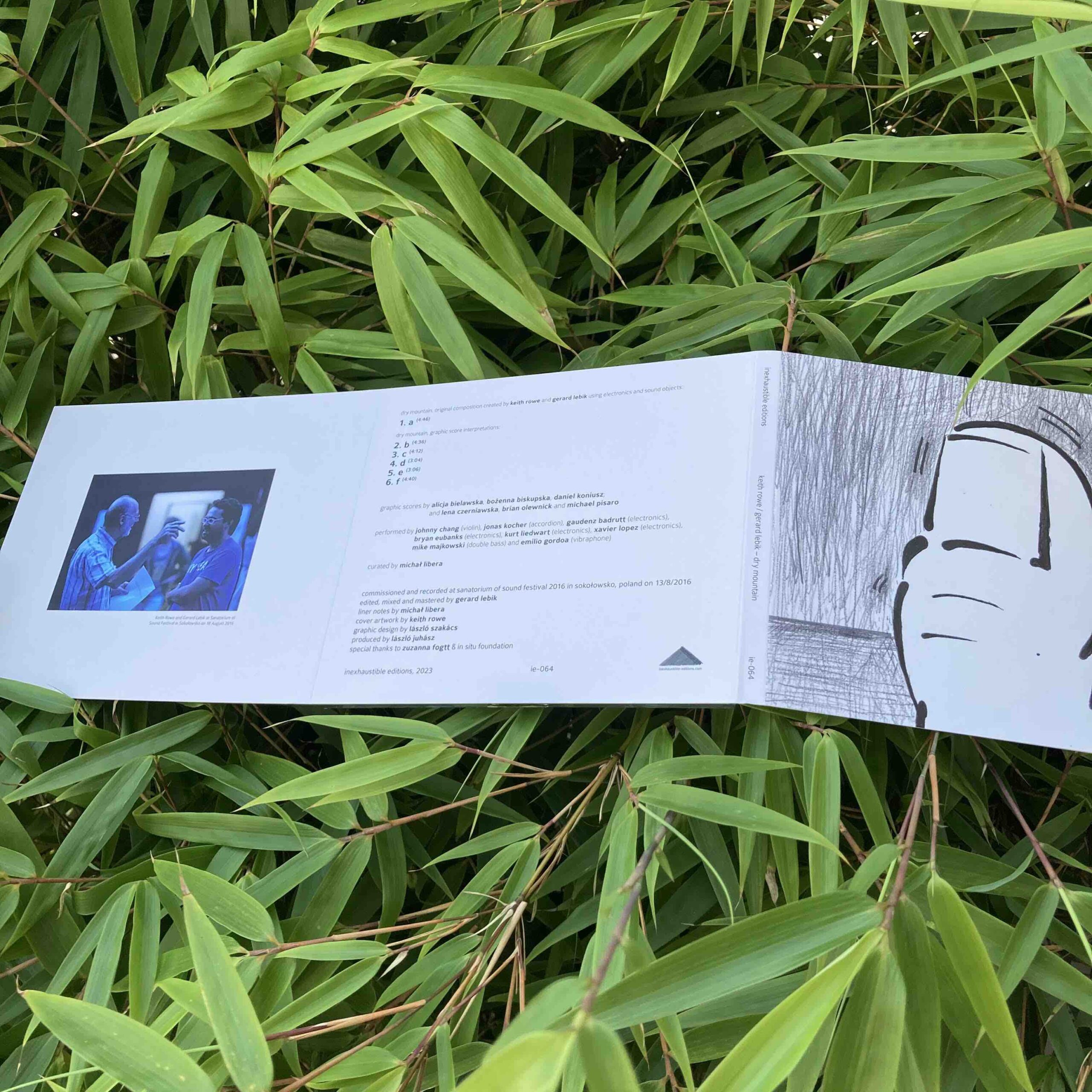

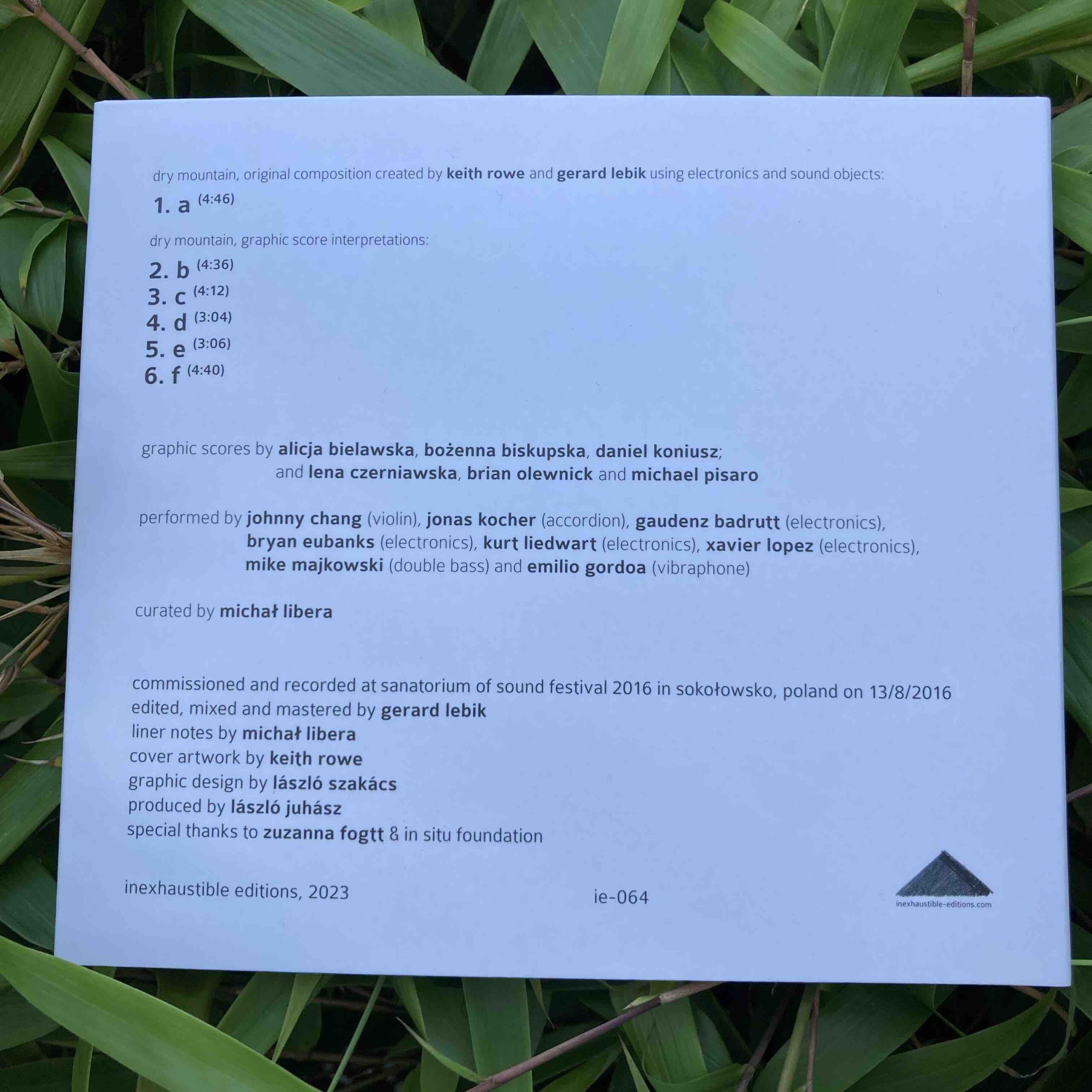

Premiered at Sanatorium of Sound Festival and released by

Inexhaustible Editions 08/ 2023 (CD)

I

„Dry Mountain” is a reflection on the form and interpretation of a musical and visual work, composition and image. The musical composition becomes the frame for the creation of the visual work and the visual work is treated as the score for the performance of the music, creating endless cycles of interpretation and reinterpretation. Initially, the musical work created by Keith Rowe and Gerard Lebik is interpreted by the visual artists invited to the project: Bożenna Biskupska Alicja Bielawska Daniel Koniusz; then the created visual representations of music are reinterpreted by musicians: Johnny Chang Mike Majkowski Bryan Eubanks Xavier Lopez Jonas Kocher Gaudenz Bardutt Emilio Gordoa Kurt Lidwart and the next scene is a real-time interpretation by Brian Olewnik Michael Pisaro and Lena Czerniawska who create drawings which are again interpreted by musicians. The project assumes the endless cycle of transition from sound to visual and visual to sound.

„Dry Mountain” is a part of “The Fall of Recording” curated by Michał Libera and Daniel Muzyczuk.

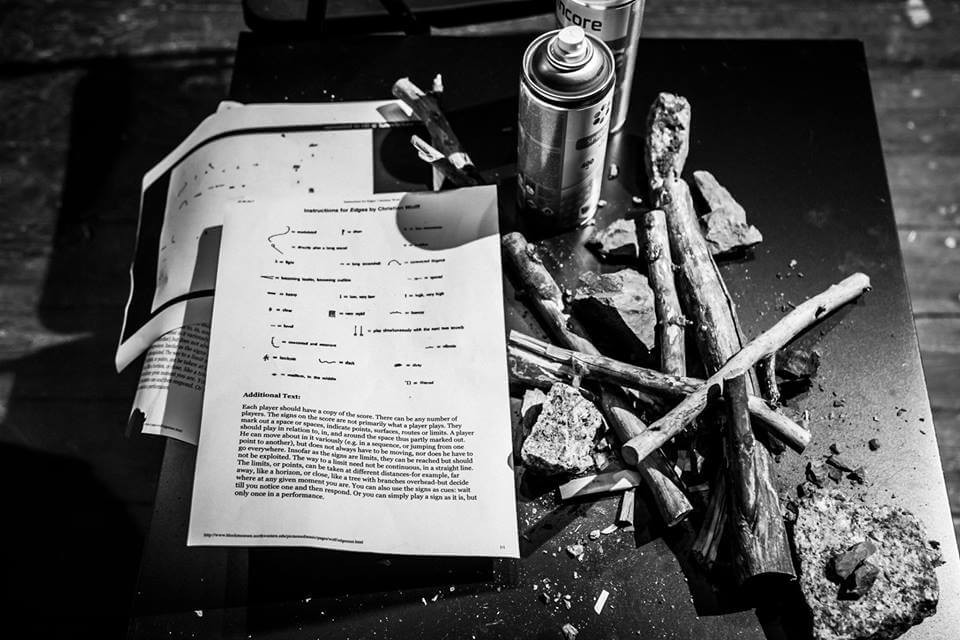

The founding element of „Dry Mountain” was a sheet of paper on which the gear of Keith Rowe stood at one of his concerts. Carrying an imprint of different weights and positions of his equipment, the paper became a score, which was later interpreted by himself and Gerard Lebik. The audio recording of that performance was afterwards handed to visual artists – Alicja Bielawska, Bożenna Biskupska and Daniel Koniusz – who created three visual scores of it, post mortem, so to say. Then the scores were performed live at Sanatorium of Sound by Kurt Liedwart and Xavier Lopez, Johnny Chang and Mike Majkowski, Bryan Eubanks and Gaudenz Bardutt, Emilio Gordoa. During the performances, Lena Czerniawska, Brian Olewnick and Michael Pisaro drawed the music they heard onto paper creating one more series of scores. Right after the concert finished, the drawings were passed to all the musicians who then interpreted the new scores on the spot, as an encore. Until now, this must have been where the spiral of „Dry Mountain” ended. With the publishing of this album, it can go on further again, forming an endless loop of scoring and performing.

Let me then add one more recording to it, inartistic. It is a private, rectangular-ish image of seemingly photographic clarity – a leftover of the only time all the above mentioned scores and performances where in one room, the Red Room of Konrad Brehmer’s Sanatorium in Sokołowsko, evening of the 13th of August, 2016. It is my own recollection, although „my” is perhaps not fully in place here since the perspective the image was taken from, in this particular context was unreachable for a human, or reachable but not for me, not then. There must be a sound to this image, too. And it also must be not in „my” ears, like the image was not in „my” eyes; unlike the image, I cannot hear it. I can see people though, in the lower part of the picture – the audience and the musicians. They are all depicted with a background of two perpendicular brick walls filling more than three quarters of the picture with their crazy red. On the right wall, there is an internal mural – a phantasmagoric, obese figure in black, violet, green and yellow. It is of rather silly appearance and unknown origin. It is also annoying, due to its completely inexplicable relation to the rest – the walls, the people, the other visual scores for the performances, the sounds that fill the air in that image. However, the more familiar I am with this picture in my memory, the less certain of it all I am. Sometimes the red of the bricks is so vivid and homogenic that it turns the people into a brown smudge, down there in the lower part of the image. At other times, the red is so greedy as to devour the infantile figure on the wall and fill all the background with one color only. But it also happened once that I thought it is rather the creature itself that has the power to disappear and reappear.

For some time I was wondering if the shape and colors of it would come back on the red wall if I played back the audio recordings of this album. But I decided not to listen to them, either because of the fear of the figure, or because of the seductive power of sounds turning the focus away from what „Dry Mountain” also can be – a prolegomena to a yet unwritten treatise on sound and memory. Perhaps the latter one would be called „Spectres of Recordings”; perhaps it would start from an analysis of sonic features of a sheet of paper, the sheet of paper on which Rowe’s gear once stood; perhaps in the second chapter it would argue for degrees of sonic presence („non-presence, semi-presence, full-presence”) in everday objects („they bare traces of music and sound they witnessed”); perhaps it would go on with many examples of materials and non-materials having a ghostly presence of sound in them, waiting to be unraveled („armchairs, clothes, thougths, breaths, bricks”); perhaps then, in the longest passage of the book, it would propose a definition of „spectres of recordings” – „sound’s ability to record itself in things, in a ghostly way” which is „as objective as notation or sound file while in the process of recording” but „completely inconclusive on the part of its reanimation in performance or playback” (of the things); perhaps it would then go on to show the viscosity of sound with objects, ideas, spaces, images, etc. – but now only to argue that the integral part of music is the very incompletness of its afterlife, the way it stays and evolves with armchairs, clothes and bricks; this „spontaneous interconnectedness” with things, ideas, images makes the same piece of music evolve with them in multiple ways; „thus – the last sentence of the treatise would state – the most objective reproduction of music needs infinite performances with renditions of ghostly spectres of recordings […] most of them being at odds with what is depicted on tapes, vinyls or in digital files”.

When asked to write this text, I was reading W.G. Sebald. In „The Emigrants” he recalls his visits to an old, dark, brick wall studio of a painter, Max Ferber: „Time and again, at the end of a working day, I marvelled to see that Ferber, with the few lines and shadows that had escaped annihilation, had created a portrait of great vividness. And all the more did I marvel when, the following morning, the moment the model had sat down and he had taken a look at him or her, he would erase the portrait yet again, and once more set about excavating the features of his model, who by now was distinctly wearied by this manner of working, from a surface already badly damaged by the continual destruction. The facial features and eyes, said Ferber, remained ultimately unknowable for him. He might reject as many as forty variants, or smudge them back into the paper and overdraw new attempts upon them; and if he then decided that the portrait was done, not so much because he was convinced that it was finished as through sheer exhaustion, an onlooker might well feel that it had evolved from a long lineage of grey, ancestral faces, rendered unto ash but still there, as ghostly presences, on the harried paper.”

At the Sanatorium of Sound festival, „Dry Mountain” has been crammed in the section of the festival called „The Fall of Recording”. It was initially conceived by Michał Mendyk, Daniel Muzyczuk and myself as a curatorial framework to imagine the era of recording as a short and relatively irrelevant stage of history which is just coming to an end. Do not technologies such as streaming or online mix give new answers to questions that brought about the faint and imperfect tools of recording? Do they not enable us to bypass recording? These were the questions we were asking ourselves. Now reading Sebald when trying not to listen to the pieces of this album, I see one more symptom of the fall of recording – it is this very melancholy of loss that shines through the writings of the German author, the drama of incompleteness, the anguish of inability to faithfully represent reality, on canvass.

Yes, all reproduction is all about loss. But can there be a way to enjoy it? Or are we doomed to always be left unsatisfied when the original in the reproduction is not quite right? There might be an answer to it in the album here, but only if you hear through the sounds and see their lives in armchairs, clothes and bricks.

Michał Libera

II

Dry Mountain Orchestra – experimental classical music 20.08.2017, including instructions from „Edges”, „Stones” and „Sticks” by Christian Wolff

Performedd by: Keith Rowe Lucio Capece Alfredo Costa Monteiro Emilio Gordoa Ryoko Akama Arnold Noid Haberl Marek Choloniewski Julien Ottavi Piotr Tkacz Barbara Kinga Majewska Marcin Barski Kurt Liedwart Klaus Filip Zsolt Sőrés Karolina Konstancja Karnacewicz Michał Libera Lukasz Jasturbczak

Premiered at Sanatorium of Sound Festival 2017

THE FALL OF RECORDING

essay by Michał Libera

with Gaudenz Badrutt, Alicja Bielawska, Bożenna Biskupska, Alessandro Bosetti, Johnny Chang, Bryan Eubanks, Emilio Gordoa, Jonas Kocher, Daniel Koniusz, Gerard Lebik, Michał Libera, Xavier Lopez, Mike Majkowski, Daniel Muzyczuk, Keith Rowe, Radek Szlaga, Valerio Tricoli

“I don’t want to die. I want to live”. Several notes placed neatly on musical staff, quite catchy lyrics, you may say, and short introduction from a composer, forms altogether almost a song. But the song written down on 26th of Febraury 1903 by a Czech composer Leoš Janáček in his notebook bears a different authorship than his own; he himself was nothing more but a recording device for an unintentional song of his dying daughter, Olga. These were her last words, and a last melody, uttered in bed just before she passed away; almost a swan song addressed to her father sitting by the bed but also to a man obsessed by the everyday passing of melodies of the world we live in. Words, noises, screams, animals and doors, hundreds of different birds and dogs and finally also his dying daughter found their ways to form short songs in his notebooks via the language of music notation. So do we know the final expression of his daughter? It’s all there, on the staff. Perhaps a song, and if so, definitely of swan kind, a document or a memoir but also an emblem of the entire myth of recording media – a song made of dying and about dying or in other words: a recorded song about recording.

The myth – or history, if you like – of recording is full of dead bodies, not unlike Olga. There is this anonymous screaming girl in the wriggling lines on paper captured by Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville’s phonoautograph. There is Adolf Hitler emerging from noises on magnetic tapes in the collection of Electronic Voice Phenomena founding figure, Friedrich Jürgenson. There is an unknown Salvadoran soldier at this very moment being buried by his son and accompanied by the little boy’s lament in the field recordings of Bob Ostertag. There are sounds of countless people who were not able to recognize their voices while listening to them played back from the wax cylinders. Not to mention the entire 27-Club on tapes, vinyls and CDs, on your computer in mp3 format or whatever else you want to keep them in, perhaps, there is also someone you actually knew, someone whose voice you heard live, your grandfather or his aunt, captured on reel-to-reel or magnetic tape, perhaps you have heard those tapes, or perhaps you didn’t, perhaps never came across them in this amorphic grand archive of recorded sounds spreading out from Library of Congress to rundown attics and computers all over the planet.

The entire history of this myth of recording, from its earliest beginnings until now, is oscillating around and preoccupied with death. The whole discourse developed around it, is a discourse about death. Some say, the dead bodies in the recordings has deprived us of the real experience of music. They say, we will never again be able to hear a live sound without it being haunted by the very possibility of being recorded. A bit like eavesdropping and bugs – there is no more innocence and disappearing in live speech. The others say, the dead bodies democratized and globalized music and our hearing. We know Beethoven’s music even if we have never visited philharmony. We know how Javanese gamelan sounds like without going to Indonesia. But whatever the range is, from fear of the dead to a sort of Halloween celebration, the myth’s main presumption is that the recorded sounds are irreducibly dead, taken out of their live context and deprived of their original setting. This is what happened in 19th Century. A fundamental and irreversible change in music and hearing caused by recording.

There is one element missing in this myth or perhaps one corpse which is never there. It is the corpse of the recording itself. This lack is crucial to the very foundation of the myth. If recording changed the music so drastically and irreversibly it is because the death of recording itself has never been thought of or imagined. If we believe the recording has changed everything, we do so because we believe it arrived for good, it will stay and never die.

***

Now think differently for a moment. Think of recording not as a mythical feature but rather a historical incident, maybe even a side effect. A phenomena which origins can be traced back in time, with has its own genealogy, its own attack and peak, decay, sustain and release. Think of now, think of early 21st century as the beginning of its last phase – not decay; release. Think of recording as a historical phenomena which did not arrive to stay with humans forever but a moment in time, actually a pretty short moment, which is now about to fade away. Think of it as a short chapter in the whole history of sound and hearing. Think differently and imagine recording coming to an end. Soon, we will not need it anymore. Already now, we are flooded with archives, redundant and overwhelming, a clueless problem rather than salvation. Already for some we are misinformed by these archives of recordings, our history is not getting and more understandable and clear, our knowledge of the once-alive people and situations is not closer to us because of the dead media.

There are good reasons to think that way. First – there are historical reasons. None of the great inventors of recording media, be it Scott de Martinville, Thomas Edison, Dziga Vertov or Pierre Schaeffer was interested or aiming at saving audio data. Even if all of them are considered godfathers of the new technology. None of them was imagining an archive and none of them wanted to become a librarian. In his diaries from 1948, Pierre Schaeffer, when imagining music concrete, did not start with the idea of recording. The other way around – recording came as an incidental or handy but at the same time disappointing solution to problems otherwise unsolvable. On his way to music concrete, Schaeffer, not unlike his avant garde predecessors, was aiming at a sampler triggering everyday sounds in real time. He called it the most general piano possible. Or noise piano. An instrument which would enable to orchestrate or play or conduct the concrete sounds rather than store them. Technologically speaking – it was impossible in 1948 and only because of that, he came up with a solution of using recorded sounds. To bypass the problem he couldn’t solve. The thing is: we can do it today. We don’t need the tape with recorded sounds.

If we go back to godfathers of recordings, we can see that the recorded sound was usually a mediocre compromise to the ideas they had. Hence, another set of reasons to believe recording will soon come to an end. These are mostly technological reasons. They seem to be both more in line with the initial ideas and completely against the path it took over the last hundred years. We know the speaking pianos of Peter Ablinger; we have the foleys and the vocal ensembles imitating field recordings; we know more literary and sensitive forms of recording of sounds then just capturing them; we now have the extended instrumental techniques and the universal instruments are reachable; we came up with streaming methods and online mixing and we imagined that records can be nothing more but just scores. With all that at hand, it is probably a high time to create an answer to an overwhelming crisis of recordings’ nostalgia, retromania and hauntology of the archives – an ontology of new realism in place of ontology of representation.

Because the myth triggered by Olga Janáček was also connecting one more element to this already rich constellation. The recorded sound became an object that meant more then the singular uttering that was presented just for a handful of ears. The voice became language of another sort, the one that is bringing meaning by the sole possibility of repetition. Thus the world of objects seen by chance by Schaeffer is a place of everlasting meaning and the terrible truth is that for this reason a reduced listening and unintentional ear is impossible. Recording means organizing and saving because the heard sound is worth something, has a potential to be of value. The world opened by this act is a world of signs, that will always bear the guilt of the necessity of having a meaning.

***

The Fall of Recording is nothing but a cloud of interests, observations and speculations we share with musicians, scholars, critics and curators. It is an ongoing research and a number of conversations, fantasies, ideas on paper, hints for possible music commissions and unresolved paradoxes. This cloud is now reaching its first incarnation at Sanatorium Dźwięku in Sokołowsko with a few (hard to count them, really) concerts and a lecture all aiming at complicating and differentiating the history of recordings cause what else can you do in the final chapter of some accidental phenomena in history?

Alessandro Bosetti will premiere a new take on his Janáček research. Already in his Ars Acustica winning piece “The Notebooks” he was dealing with hundreds of notated speech melodies of a composer who did what we are doing with our recording devices. His’ was a pen and a staff. This recording obsession of his lead to dozen of notebooks kept in Brno which are literary field recordings.

Keith Rowe’s Dry Mountain project originated in Sokołowsko and came into being as a painterly recording device. A short piece of music recorded together with Gerard Lebik served as reference point to four visual artists commissioned to score it. Now four duos will perform the very same piece of four different scores simultaneously, in open air.

Finally Valerio Tricoli’s premiere deals directly with the aforementioned diaries of Schaeffer. Taking his memoir of 1948 as a sort of guideline through a piece, he prepared a hybrid performance using the recorded sounds of Schaeffer – both the sounds he was using in his research and his voice – for and against his methodology of music concrete.

Michał Libera (1979): sociologist working in sound and music since 2003, now mainly involved in producing and staging sound essays and other experimental forms of radio art and opera which brought him to collaborate with Martin Küchen, Ralf Meinz, Rinus van Alebeek, Alessandro Facchini, Joanna Halszka Sokołowska, Komuna// Warszawa and others. Libera is a producer of conceptual pop label Populista dedicated to mis- and over- interpretation of music as well as series of reinterpretations of music from Polish Radio Experimental Studio (Bôłt Records). He curates various concerts, festivals and anti-festivals, music programs for exhibitons and received honorary mention at 13th Venice Arhcitecture Biennale. Other regular collaborators include National Art Gallery Zachęta, Centre for Contemporary Art in Warsaw, Polish National Museum (Królikarnia), Galerie West in The Hague, Satelita in Berlin. His essays on music and listening „Doskonale zwyczajna rzeczywistość” were published by Krytyka Polityczna. »